Education Resources for Teachers and Students

Download the full education kit here

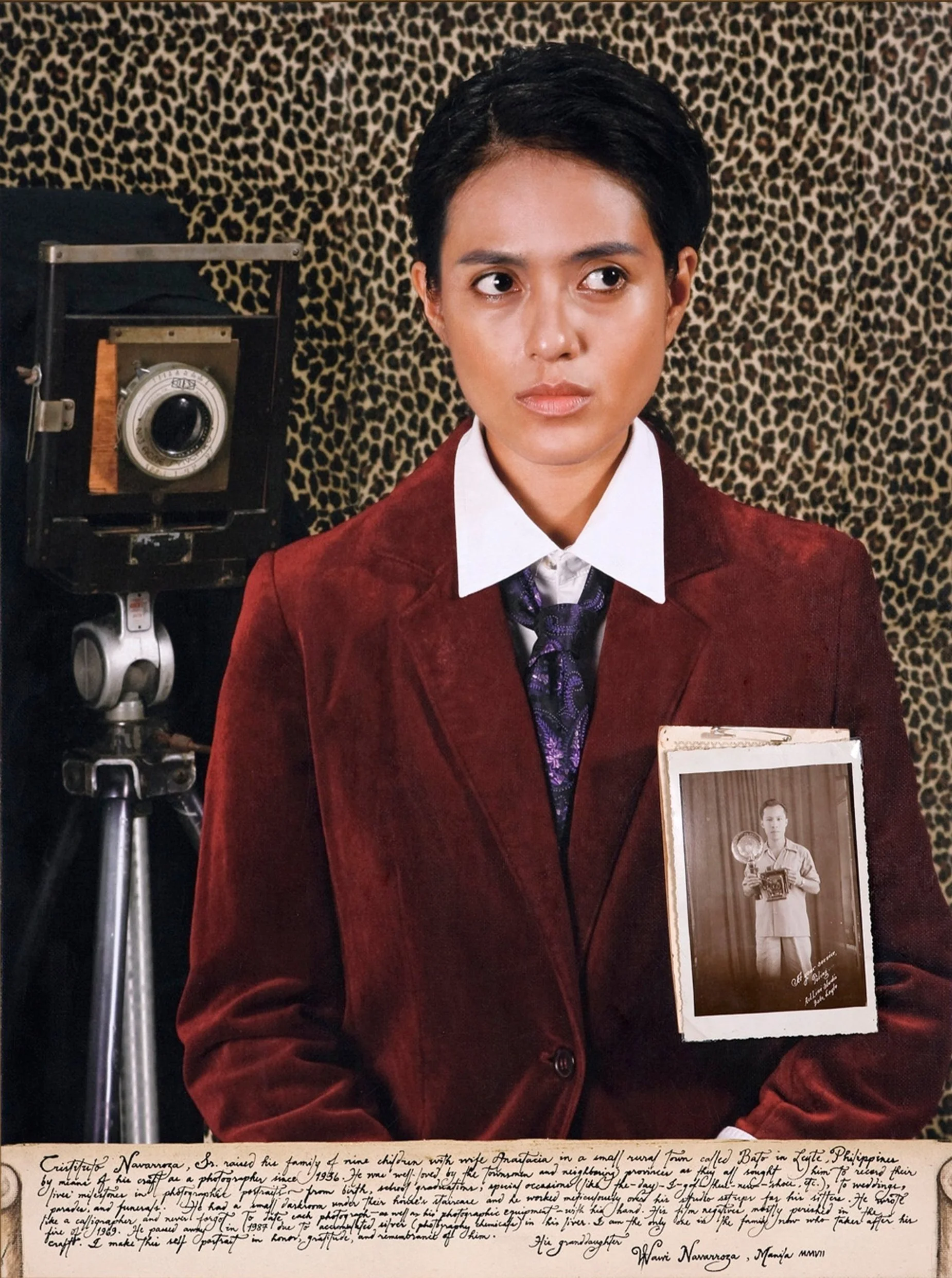

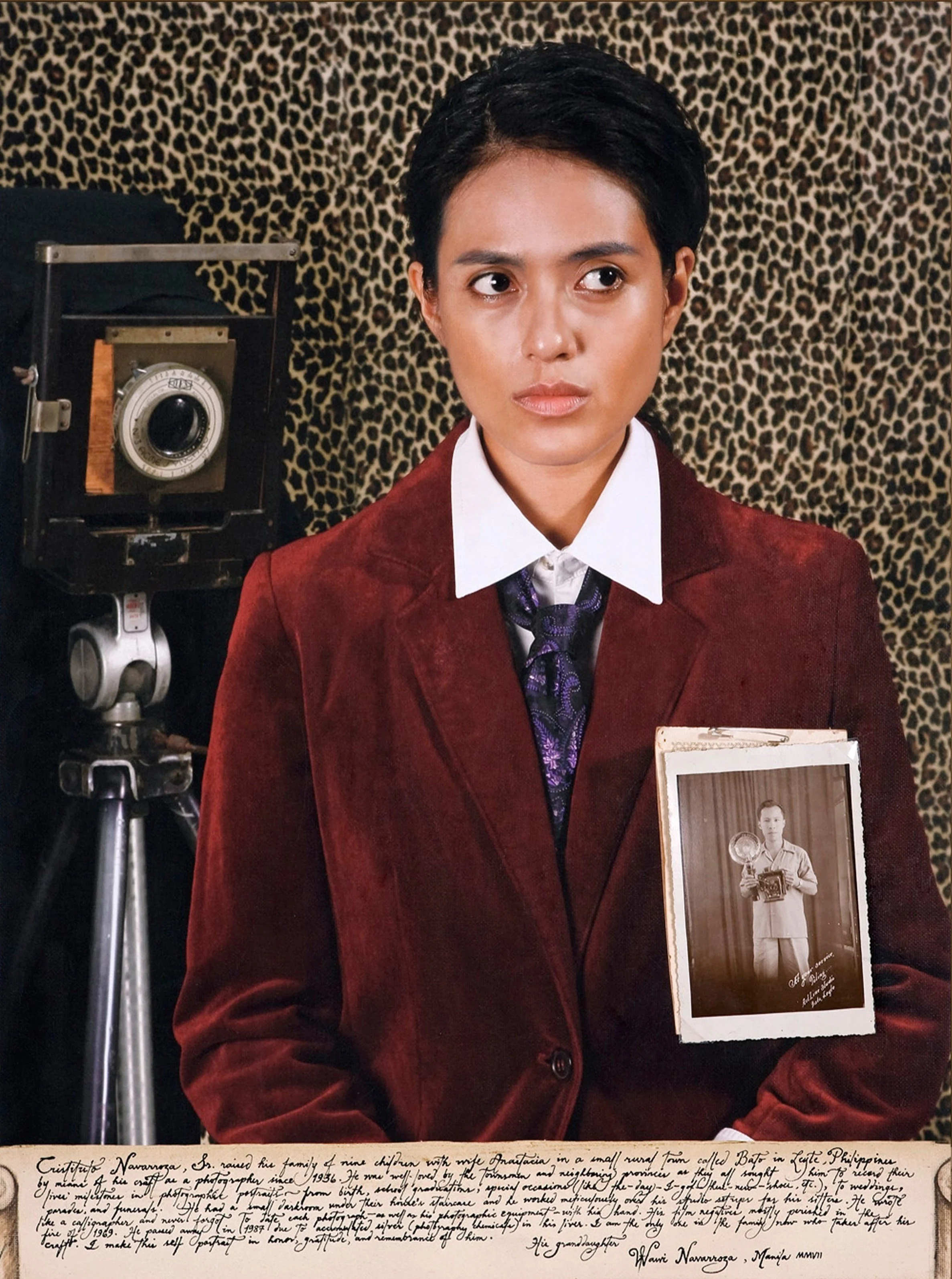

Wawi Navarroza, Self-Portrait for My Grandfather, the Photographer (after Frida Kahlos Portrait of My Father / Retrato de Mi Padre, 1951) 2007, Lambda C-print, 61 x 45.7 cm

Our Grandfather Road: The (gendered) body and

place in contemporary southeast Asian art

These resources are designed for students in Years 11 and 12 studying Visual Arts through either the NSW Preliminary and HSC or IB syllabuses. They may also be useful for tertiary students from different disciplines visiting the exhibition. They aim to provide interesting entry points through which teachers and students can engage with works in the exhibition, and suggestions for more in-depth case studies.

The five artists selected for particular focus indicate the rich diversity of practice among contemporary artists in southeast Asia. They employ media ranging from painting, drawing and printmaking to photomedia, video, installation and street art, revealing aspects of their personal, social, cultural and political worlds. Questions and activities invite students to engage with the material and conceptual practice of the artists, to consider the themes that emerge from the exhibition’s curation, and to make significant connections with their wider study of contemporary art.

Scroll down for suggestions and activities for teachers and students.

An Introduction to the Exhibition

Our Grandfather Road presents seventeen artists whose work is as diverse as the region itself. Sixteen women artists and one trans-masc artist from Singapore, Indonesia, Thailand and the Philippines explore themes of gender, cultural and social history, and spatial/temporal experiences. Inevitably in this complex contemporary world, tensions emerge. Local issues are refracted through their global implications, whether that be the impact of the pandemic, the loss of orangutan habitat in Borneo, the alienation of public and private spaces at the hands of property developers in Singapore, access to education for women and girls in Indonesia, defiance towards the military junta in Myanmar, gendered power relationships in Thailand, or abuses of power in both private and public settings everywhere. These are personal narratives of joy and sorrow as the artists navigate past and present geographies of space and time.

The exhibition takes its title from a work by Singaporean artist Sam Lo. Lo’s photograph records the words “My Grandfather Road” spray-painted onto a street in Singapore’s Central Business District. The Singlish phrase, used colloquially to berate people for obstructing others in a public space (‘you think this is your grandfather’s road?’), is repurposed here as a way of reasserting a sense of place, heritage, and belonging in the face of rapid urban development—a phenomenon particular to Singapore but common to all major cities of Southeast Asia, and often a source of alienation or regret for local populations. The title, then, which substitutes “our” for “my”, serves a dual purpose. Lo’s work asks us to imagine that what is “mine” could very possibly be “ours”.

Curatorial Statement

Our Grandfather Road develops its conceptual premise along the intersecting axes of gender and geography. Yet, in more ways than one, the diversity of artists represented in the show trouble and reimagine the entangled, contentious concepts of ‘gender’, ‘womanhood’, and ‘southeast Asia’.

To even attempt to categorise the exhibition as a “woman’s show” reveals the limitations of gender as a thematic descriptor. Sam Lo (Singapore), for example, whose photographic series Our Grandfather Road (2012-16) inspired the exhibition’s title, has since transitioned to a trans-masculine identity, despite being memorialised in popular culture as Singapore’s ‘Sticker Lady’. Other artists, who have already experienced considerable success in the international art world, such as Arahmaiani Feisal (Indonesia) and IGAK Murniasih (Indonesia), have rejected attempts to label them as feminists, considering the term to be part of a Eurocentric, neoliberal discourse which oversimplifies the conceptual richness of their practices. It is also worthwhile to note the inclusion of more recent works produced within the last three years. The Burmese artist Emily Phyo’s striking photograph of a three-finger salute, transposed from a dystopian fiction trilogy to become a real symbol of protest in contemporary Myanmar, documents the imbrication of human lives in a landscape of political turmoil and repression. Fitri DK (Indonesia) records the presence of indigenous women’s bodies at the frontlines of land disputes in Indonesia in a series of black-and-white woodcut prints; and, although visually distinct, Kasarin Himacharoen’s (Thailand) vibrant, miniature prints of women’s bodies in rest, contemplation, and motion, and Ipeh Nur’s (Indonesia) largescale black-and-white batik, each speak to the impact of a global pandemic on (women’s) bodies, minds, and spaces of interiority.

Kasarin Himcharoen, Untitled 2019, colour etching, 15 x 11 cm

For Teachers

Our Grandfather Road presents exciting opportunities to integrate new works by artists from the Asia Pacific region into existing curricula and case study investigations. This resource presents information, questions and suggested activities in relation to the exhibition as a whole and in more detail to five of the seventeen artists. They can be accessed before, during or after a visit to the gallery.

This resource is linked to syllabus content and outcomes from the NSW Preliminary and HSC and the IB Diploma. It may also be helpful for tertiary students and teachers who might engage in more in-depth discussions in or beyond the gallery. Fine Arts and Art Theory undergraduate students and postgraduate students in Curating Masters programs may enjoy discussing the focus questions, which range in degree of difficulty and sophistication.

Questions and activities can be easily adapted to the specific needs of students and teachers in their individual contexts. The questions provided in this resource may be used for written responses, examination preparation, or for open-ended discussions in the gallery or the classroom.

Suggestions for Teaching and Learning

Consider examining the exhibition as an in-depth focus study within a broader investigation of Art & Place, Art & Identity, Art & Gender, or Art & Feminism. Alternatively, select one or more artists or artworks for a close analysis, examined through a particular theoretical lens (e.g., Artist’s Practice, the agencies of the Conceptual Framework, one of the Frames or from within the artist’s particular local context).

An Example: Art and Feminism, a Case Study

Students investigate the Western history of feminist art in Euro-America, including the work of Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro, and the pioneering 1971 essay by Linda Nochlin, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?”

They consider this history in relation to the survey exhibition of Australian artist Vivienne Binns at the Museum of Contemporary Art, and/or the two iterations of “Know My Name” at the National Gallery of Australia in 2021, and/or to historically significant exhibitions of women artists such as “Wack!” (2007, MoCA, Los Angeles) or “Global Feminisms”(2007, Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, Brooklyn Museum).

They might look comparatively at works by artists such as Tracey Emin, Sarah Lucas, Louise Bourgeois, Barbara Kruger, the Guerrilla Girls, Martha Rosler, Wangechi Mutu, Lorna Simpson, Lin Tianmiao, Tao Aimin and/or Liu Xi. They might consider the work of non-binary or gender non-conforming artists such as Lu Yang, Kent Monkman or Juliana Huxtable in relation to the work of Sam Lo.

Finally, students select one artist from Our Grandfather Road and examine their practice in detail.

NSW HSC Syllabus Focus: Art Criticism/Art History

Artists’ Practice, Conceptual Framework (Artist/Artwork/World/Audience)

International Baccalaureate Diploma Syllabus Focus: Visual Arts in Context

Theoretical Practice: Students examine and compare the work of artists from different cultural contexts.

Curatorial Practice: Students develop an informed response to work and exhibitions they have seen and experienced.

Questions for discussion could include:

What is feminist art?

Why do some artists in this exhibition – and others – reject a feminist identity?

Does an artist have to be a feminist to make feminist work?

Does gender still matter in the artworld?

Is there a role for women-only exhibitions?

Is contemporary art local or global?

Can/should artists be activists?

Useful Links:

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/f/feminist-art

https://www.theartstory.org/movement/feminist-art/

https://www.moma.org/collection/terms/feminist-art

https://www.moma.org/magazine/articles/685

https://artsandculture.google.com/story/the-feminist-artists-whose-work-you-need-to-know/AQURUC6SwwhEKw?hl=en

Questions Inviting Written Responses:

How do contemporary artists explore ideas about identity in their artworks?

Examine the work of two artists who explore issues of place and/or gender in their work.

For Students

Here you will find brief information and some focus questions about 5 artists from Our Grandfather Road. You can deep dive into researching individual artists, or compare and contrast their work with others, considering how they respond to local and global issues.

About contemporary art

in southeast Asia

Eluding simple definitions or falsely universalising connections between distinct histories and cultures, the art of southeast Asia is vibrant, dynamic and complex, bearing traces of “the rise and fall of kingdoms and empires, and … the historical traces of colonisation and the often-traumatic birth of nations.”1 Artists from Indonesia, Cambodia, Thailand, Myanmar, Laos, the Philippines, Vietnam, Singapore and Malaysia explore local and global themes including personal and national identity and community, cultural knowledge, power, faith and the increasingly urgent impact of humans on fragile ecosystems.

Find out more

https://theartling.com/en/artzine/artist-defined-contemporary-southeast-asian-art

https://artsandculture.google.com/story/no-country-contemporary-art-for-south-and-southeast-asia-solomon-r-guggenheim-museum/1QUh-qBV5YVyKQ?hl=en

https://www.sothebys.com/en/articles/five-of-the-most-influential-women-artists-from-southeast-asia

https://artradarjournal.com/7-influential-women-artists-from-asia-pacific/

Joan Kee (2011) Introduction Contemporary Southeast Asian Art, Third Text, 25:4, 371-381, DOI: 10.1080/09528822.2011.587681 at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/09528822.2011.587681

1 “No Country: Contemporary Art for South and Southeast Asia”, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and Foundation

Arahmaiani Feisal, Tatapan Gadis 2004, acrylic on canvas, 150 x 100 cm

Other Education Resources: